Acqua - Implimenting Datatables

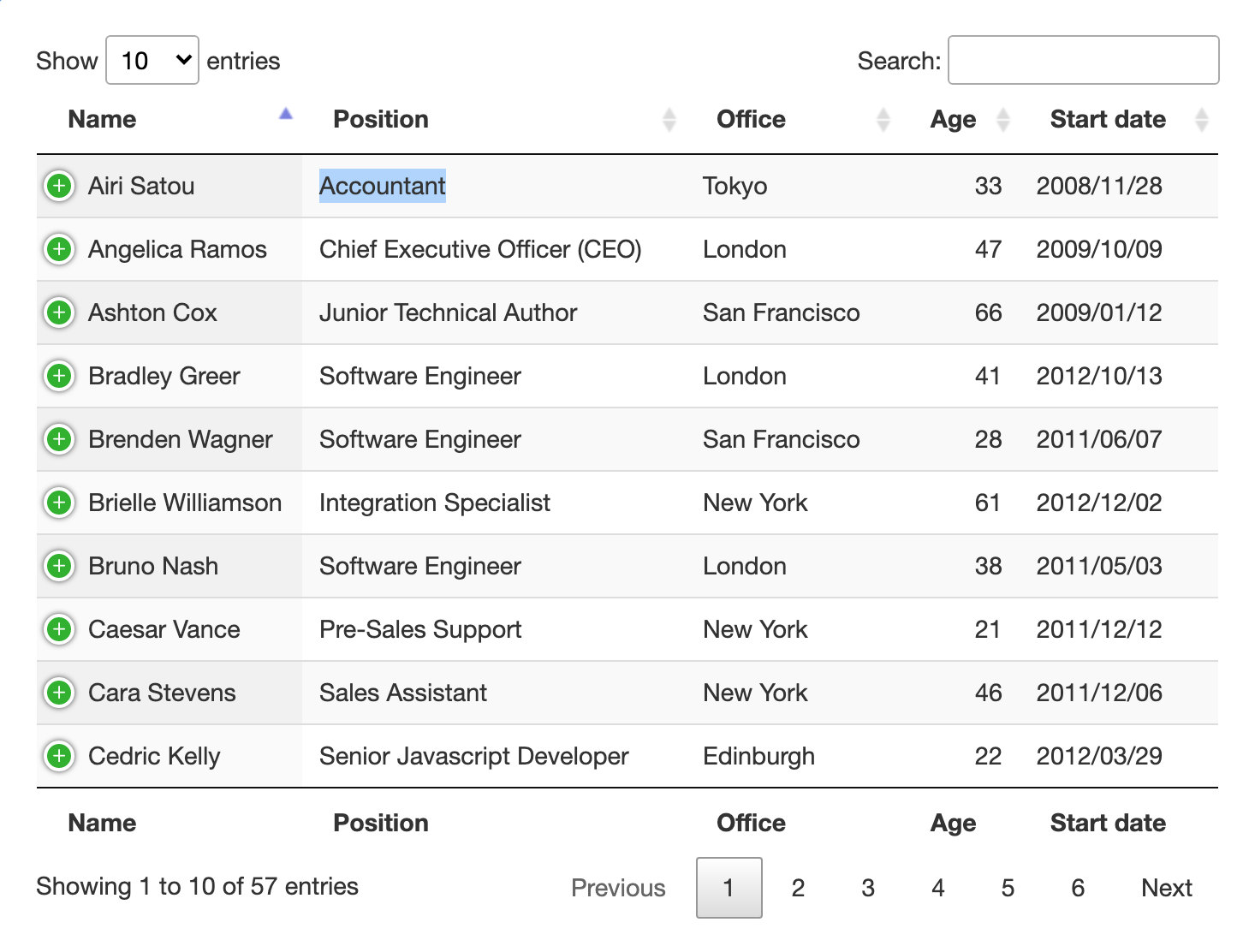

Datatables Library

I’ve been slowly working through my list of TODOs on the Acqua project, which for the initial alpha release is just a basic functional outline. I decided to initially focus on getting a manual data storage / display interface up and running as this could then easily be extended by automating the data storage aspects, plus I wanted a way to include manually entered records as there’s a good use case for this when implemented as an aquarium controller as in addition to automated data acquisition manual water parameter tests are also carried out. Presently I use a program called aquarium live to record and manage these test parameters so it seemed like a good idea to be able to cater for manually entered data, plus an easy pathway into developing the app.

After getting the basic navigation interface working I came across some bootstrap examples including this Bootstrap 4 example for a company dashboard. It encompassed all of the elements I wanted to use in the basic trend data overview, a list of trends on the left, the trend itself, displayed as a graph and the trend data records. Whilst Flask-bootstrap does not support bootstrap 4 out of the box, and the Bootstrap 3 version does not include the awesome chart, I decided that I could make it work so included it in acqua as the basis for the trends page.

With the last commit I managed to get the trend list working as a basic CRUD action (TBH I still have to do the ‘update’) and so with this commit I have been focusing on getting the data table view working. This has involved expanding on the initial SQLAlchemy database functions and jekyll template handling to include the additional fields required for creating the datatable.

Jekyll - The View

Essentially the front end template or the ‘view’ part of our MVC setup includes a for-loop that iterates through the trend data which is passed to the template as an array of records. Here’s the code from the template:

/acqua/application/trends/template/trends.html

<table id="datatable" class="table table-striped table-sm">

<thead>

<tr>

<th>#</th>

<th>Date</th>

<th>Trend Type</th>

<th>Value</th>

<th>Units</th>

</tr>

</thead>

<tbody>

{ % for trend_data_entry in trend_data % }

<tr>

<td>{ { trend_data_entry.id} } </td>

<td>{ { trend_data_entry.timestamp} } </td>

<td>{ { trend_data_entry.trend_type} } </td>

<td>{ { trend_data_entry.value} } </td>

<td>{ { trend_data_entry.unit_of_measure} } </td>

</tr>

{ % endfor % }

</tbody>

</table>

The magic is happening in the ` { % for trend_data_entry in trend_data % } … { % endfor % }` statement which acts much the same as a traditional for-next loop where you would use the loop count to index the array position of the variables, except that with Jekyll there’s no array index needed, it automagically takes care of all of that. The Jekyll templating datatypes are very reminiscent of the templating functionality I developed in my DeeEmm CMS (DMCMS) and are a very powerful way to bring backend processing into HTML, although I do wonder if half of the Flask-Jekyll-SQLAlchemy-Bootstrap implementation is little more than code masturbation, after-all, what was wrong with plain old HTML, CSS and backend processing, more on that in a seperate rant when I get to it :D

But I digress.

This iterative processing of the SQL query result passed to the template engine via the trend_data entry, is parsed by the for-endfor loop, which breaks out each result into the trend_data.sql_column results seen, allowing them to be easily used as table data one row (result) at a time.

The Controller (our endpoints)

Let’s take a look at what’s going on in the back end. This is our trends.py blueprint file, essentially the ‘controller’ in our MVC layout.

/acqua/application/trends/trends.py

from flask import Flask

from flask.ext.sqlalchemy import SQLAlchemy

...

from application.trends.models import db

from application.trends.models import Trends

from application.trends.models import Trend_Data

# Blueprint Configuration

trends_bp = Blueprint(

'trends_bp',

__name__,

template_folder='template',

static_folder='static',

static_url_path='/trends'

)

@trends_bp.route('/trends', methods=["GET", "POST"])

def trends():

with app.app_context():

trends = `Trends.query.all()`

trend_data = Trend_Data.query\

.join(Trends, Trend_Data.id==Trends.id)\

.add_columns(Trend_Data.trend_id, Trend_Data.timestamp, Trend_Data.value, Trends.unit_of_measure, Trends.trend_type)\

.filter(Trend_Data.id == Trends.id)\

return render_template("trends.html", trends=trends, trend_data=trend_data)

I’ve removed some code for brevity, so the above example differs from the committed version but essentially what’s going on here is that the /trends endpoint calls the code to grab the database values it needs. Lets break it down…

trends = Trends.query.all()

Here we run the equivilent of an SQL SELECT ALL FROM TABLE 'Trends' statement and store the results in the trends variable, which is essentially an array.

.join(Trends, Trend_Data.id==Trends.id)\

The join function works the same way as a traditional SQL LEFT JOIN which joins the id fields of the Trend_data and Trends tables.

.add_columns(Trend_Data.trend_id, Trend_Data.timestamp, Trend_Data.value, Trends.unit_of_measure, Trends.trend_type)\

Here we specify what data we want to use from the join.

return render_template("trends.html", trends=trends, trend_data=trend_data, release=release, version=version)

And here we create the jekyll template variables that will be used in the front end, note the trend_data variable we used above in the for-endfor loop in the template - this is where it originates.

In short, when the ‘/trends’ endpoint is called, we pull the data from the database and assign it to variables which we can use to parse the template engine.

So that’s the template engine (the ‘View’) and our main code (the ‘Controller’) but there’s still one more aspect to take a look at, the ‘Model’:

The Model

/acqua/application/trends/models.py

from application.database import db

# Trends - id | type | description | unit

class Trends(db.Model):

__tablename__ = 'trends'

id = db.Column(db.Integer, unique=True, primary_key=True, )

trend_type = db.Column(db.Integer)

description = db.Column(db.String(80))

unit_of_measure = db.Column(db.String(80))

def __repr__(self):

return "<Trends: {}>".format(self.description)

# Trend_data - id | trend_id | timestamp | value

class Trend_Data(db.Model):

__tablename__ = 'trend_data'

id = db.Column(db.Integer, unique=True, primary_key=True)

trend_id = db.Column(db.Integer)

timestamp = db.Column(db.String(80))

value = db.Column(db.String(80))

def __repr__(self):

return "<Trend_Data: {}>".format(self.value)

db.create_all()

This is the trends/models.py file in its entirety. The applications\database.py file called at the top is where the database connection is created, I call this in all of the models used. This was a bit of a stumbling block for me as I was originally trying to set up the database in my init.py file, not realising that program flow is not really end to end in flask. This resulted in empty database instances and left me with a lot of head-scratching trying to figure out why I was getting errors.

If you read my last post you may have sensed some dismay at implementing the CRUD functionality. This comes from the way that python / flask handles inheritance, which is simply that it appears to completely ignore it, even when explicitly declared. So breaking functionality out into seperate files, for example as in a traditional Model / View / Controller architecture was not straightforwards when you have a procedural mindset like me. This is also despite the fact that such layouts are promoted as part of the ‘blueprint’ system that flask uses, they even give a nice example of an MVC folder / file structure in the documentation but they do not explain how to actually pass data between these seperate files, the documentation leaves a lot to be desired. This also seems to be the same with all of the examples online, where everyone gives a code snippet, but no one explains where these snippets reside and how they interface with each other, no files names are mentioned and no import statements explained.

The BIG issue that I had was that despite importing that relevant database instances, the database object was empty and this did not seem to make much sense. it was only when I broke the database creation out into the Model by moving db.create_all() from my init.py file into models.py and I explicitly imported each database object into my trends.py controller that things started to work. Looking at the examples above, pay particular attention to the file-paths, database classes and the import statements…

from application.trends.models import db

from application.trends.models import Trends

from application.trends.models import Trend_Data

And just to note the folder structure is as follows… (you can see it on github too)

Application

|-trends

|-trends.py

|-models.py

|-templates

|-trends.html

database.py

__init__.py

Other functions also sit within the application folder and follow the same layout as the trends function.

So in the Model what we are doing is creating individual ‘models’ of the database, each of which represents a specific table. Here’s the ‘trends’ table:

class Trends(db.Model):

__tablename__ = 'trends'

id = db.Column(db.Integer, unique=True, primary_key=True, )

trend_type = db.Column(db.Integer)

description = db.Column(db.String(80))

unit_of_measure = db.Column(db.String(80))

def __repr__(self):

return "<Trends: {}>".format(self.description)

The above snippet sets up a database model class for the ‘Trends’ table and creates methods for each of the columns / fields. This way the fields are available as methods to the rest of the program. I find this to be genius, but also find it completely annoying as I consider wrapping SQL like this is completely unnecessary. JUST LEARN SQL DAMMIT. lol. (another rant for another day)

So now all of the database fields are accessible from the Trends class object, which is utilised in the Trends.query.all() calls within the main controller file trends.py

So I think in general that there’s a lot of code masturbation going on here. We have the SQL wrapped in a class, courtesy of SQLAlchemy, this is then assigned to variables in our controller courtesy of Flask and this is then assigned to other variables in the template courtesy of Jekyll which is then rendered courtesy of Bootstrap, Charts and Datatable libraries. Our reliance on libraries is getting ridiculous. Even the traditional MVC layout is not exactly minimalist. There’s lots of files and folders where there could be just one. I’m not 100% sure I like it, as it all seems largely superfluous to me. We are using thousands of lines of code to do work which could be implemented with less than a hundred. It is far from pragmatic. I will get around to writing a post about this at one point. But again, I digress.

So that’s how I have laid out the basic Acqua MVC architecture. I’ve tried to follow generally accepted norms. I haven’t broken out the models and controllers into dedicated folders simply as for this application there will only be one file for each function, but on a larger project you would probably consider doing this for readability. I really hope this helps save someone from the same pain and agony I endured trying to figure out why I could not get my database to work. The solution was ironically quite simple and I’m sure that the python gurus out there reading this are shaking their heads, but then everything is easy once you know how.

If you want to see a working example of this, take a look at the github repo

As with all of my posts. If you have found it useful, I don’t ask for beer, coffee or patreon donations, just pay it forwards with a random act of kindness.

/DM