DIY Extruder screw making machine Part 1 - The table

In my last post Improvements to a wood auger based plastics extruder I discussed an idea to make a simple machine using hand tools from which an extruder screw could be made. The basic premise of the machine is that it can be built using easily obtainable parts using methods that are accessible to everyone.

Of course, by far the best way to build an extruder screw is on a CNC machine, however this is such a specialised piece of equipment that very few people have access to one. This means that the only option to own such a screw would be to buy one already made, or engage someone to make one for them, neither of which is a cheap endeavor and in some parts of the world is simply not an option. So being able to make one from hand tools is the ideal methodology as hand tools are cheap and accessible to almost everyone.

However using hand tools to create something which needs to be relatively accurately made is not without inherent problems. The issue with hand tools is that accurate results take a lot of effort and the possibility of mistakes is also very high. For trades people and artisans accurate results are a matter of pride and are borne of experience, however for those who have little experience and have yet to develop such skills, the possibility of producing good results is somewhat reduced. So the idea is that by using hand tools we can make a manufacturing aid that assists the machining of the screw. With careful design it can produce a quality in results far in excess of those used to build the machine itself

After doing some pondering and preliminary sketches, and getting a bit of input from the PP community, I changed the design a little. My original idea was to have the workpiece mounted next to the grinder table and coupled with timing belts, but after a suggestion of mounting it inline with the table I decided that this was a better layout as it reduces the number of parts required, which in turn reduces complexity and build time, and also improves reliability (less parts means less things to fail - machine building 101).

So armed with an idea and the need for a trip to the local hardware store I went and purchased the parts I needed to make the machine.

NOTE: Disclaimer: The machine design uses powered hand tools. I know that technically these are not available everywhere, but if you take into consideration that to operate the finished machine you require some form of power, using powered hand tools is fine.

Ingredients

What I ended up with is this:

- Long wood auger bit

- 2 x drawer runners

- Metal gate hinge

I also had the following in stock

- Round (bright) bar

- 50mm steel RHS (actually an old bed frame)

- 40mm steel angle

- 50mm flat bar (I had 40mm but if you are using this a shopping list 50mm is better)

You will also need the following hand tools.

- Drill or drill press

- Drill bits

- Hand held grinder - you will use this in the finished machine but can also use it to cut the metal to make the machine

- Grinding and cutting discs

- Files - to remove burrs and sharp edges

- Welder.

NOTE: It is totally possible to make this without a welder. All welded joins can be substituted for brackets and nuts and bolts or tek-screws, however using a welder makes it stronger and quicker to build.

How it Works

The machine is basically a table that moves when you turn a handle.

The table holds a grinder.

The handle rotates the workpiece as the table moves the grinder along it.

The rate at which the table moves along the workpiece and the speed of rotation of the workpiece is exactly the same as the wood auger

The result is that the workpiece is ground / machined as a facsimile of the auger.

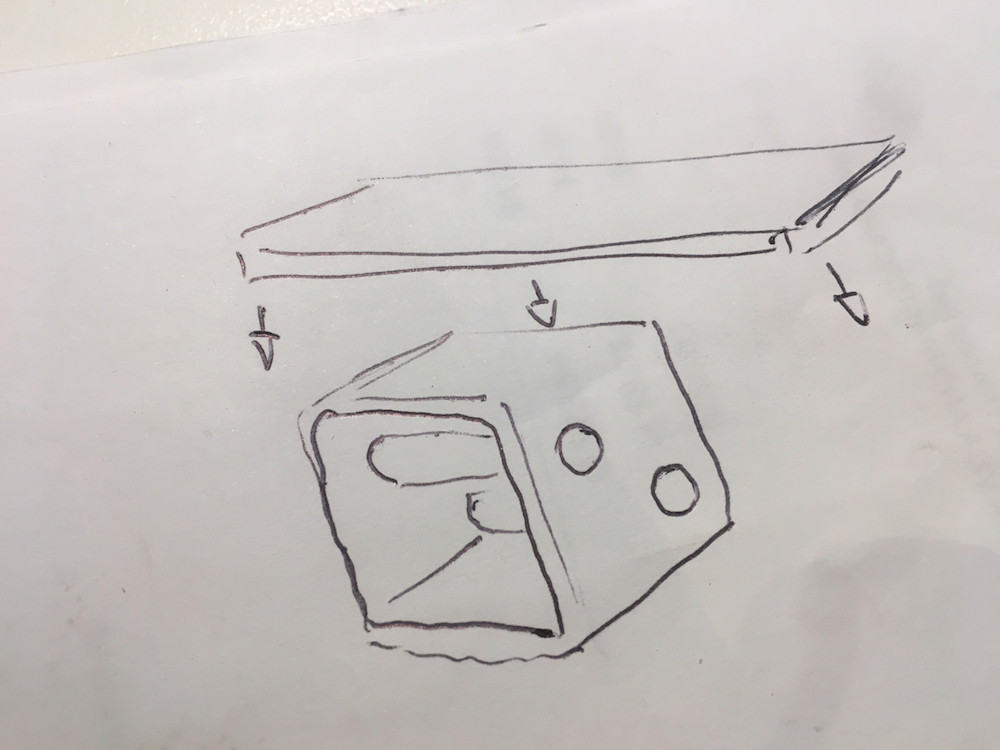

An additional guide profile is used to set the height of the grinder

Varying the height of the grinder along the workpiece length changes the screws root dimension producing the load / compression / metering zones

Method.

The trickiest part of the entire build is the 'nut'. This is the part that the wood auger engages into to turn the augers rotational motion into linear motion. It is effectively the same as a nut that you would use on a bolt, however it looks nothing like it. The challenge with manufacturing something that would thread onto the auger bit is that it is a very complex shape that would itself require some specialist machine, however, in practice this is not actually necessary.

If you turn the auger in your hand you can use your finger to follow the path of the 'thread' along the auger as it rotates. What if you replaced your finger with something more substantial, such as a metal pin? Would that not also work? It actually works quite well. Very well in fact. So to create the 'nut' you need make a bracket that holds the pin in position against he nut as it rotates. I decided to use two pins, one above and one below the auger so that the nut could not 'skip' along the 'thread'. These pins need to located relatively accurately, too much of a gap and the mechanism would become sloppy.

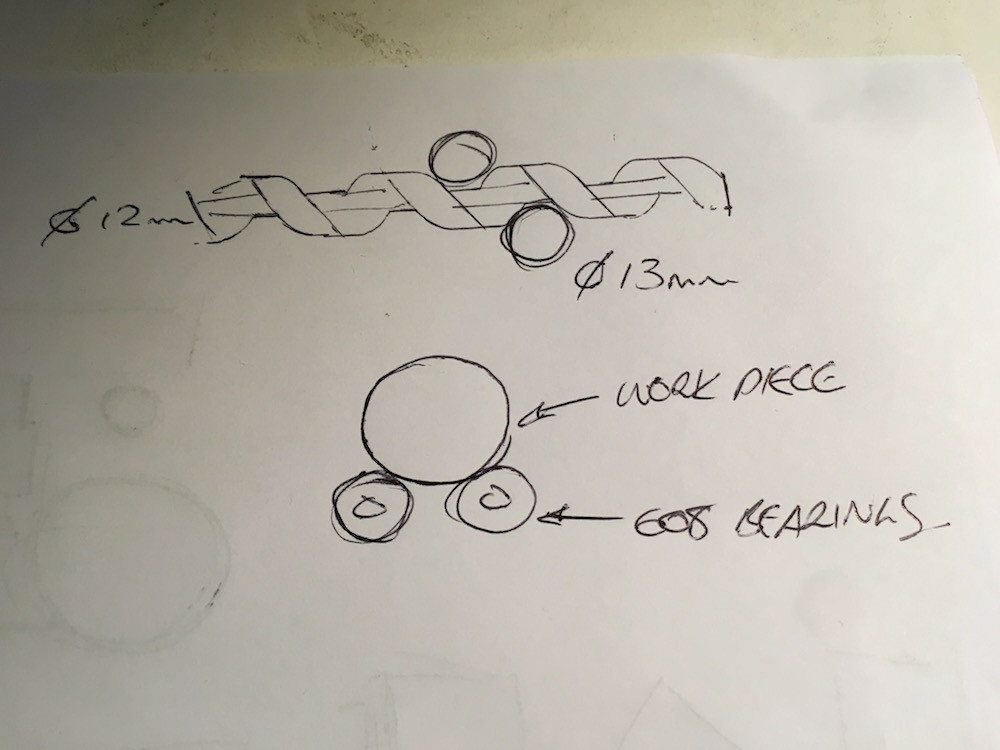

The first thing to find out is what size pins you need. These pins will need to be a different size depending on which size aguer you use. The easiest way to do this is to use your drills and place them into the 'thread' of the auger to find the best size. Ideally it does not want to touch the root of the thread (the innermost part).

You will also want to take the very edge off of the auger bit as it will be quite sharp, you can do this with the grinder or a hand file. This will allow the mechanism to work a bit easier.

Once you have found out what sized pins you need you can use the drill to make a template to mark out the holes for the sides of the nut. Simply place the auger bit squarely onto some paper, put some ink or paint onto the end of the drill bit and then mark the paper by placing the drill bit into position in the auger. Mark both the top and the bottom of the auger. Now you can use this pattern to mark out the sides of the nut. Essentially you need two holes to retain the pins that engage with the threads.

I will confess that I decided to be a little tricky and add bearings to my machine as the pins rotate when the auger turns. This is something that I identified when I came up with the original design. I also turned spigots on my pins to fit into bearings that I already had, which is obviously moving away from the 'make it with hand tools' philosophy. My excuse here was that if I had the opportunity (and patience) I would simply have ordered bearings of a size that the pins fitted through without the need to machine them. But I'm impatient and I have a lathe, so I cheated. But you could also use a nut and bolt with a length of tube or something similar instead, that would negate the need for a lathe.

That said, in practice I don't think the bearings are actually necessary, and it did create a little bit of a problem (more on that later), but then that's what prototyping is all about. I think that the pins will work fine without the bearings, so do not do what I have done, instead simply make the holes the same size as the pins - eg if you have a 10mm pins, just drill 10mm holes. There will be enough clearance for the pins to rotate and given the speed that the pins rotate at, ball bearings are not actually necessary, a little oil or grease will suffice. The mechanism will be stiffer to turn, but if you are only making one or two screws, I don't think that this will be an issue.

So once you have drilled out the side brackets for the nut you can then join them together. I made my nut from two pieces of angle, joined together with a bit of flat bar across the top, but it's probably better to make it from a bit of RHS with the auger running through the middle as it will be much simpler to assemble. The angle requires you clamp and align it, and in my case I welded it all together. By using RHS you simply thread the auger through the centre and then align the pins through the holes in the side. The entire assembly can then be dropped into the frame, which keeps the pins captive in the RHS.

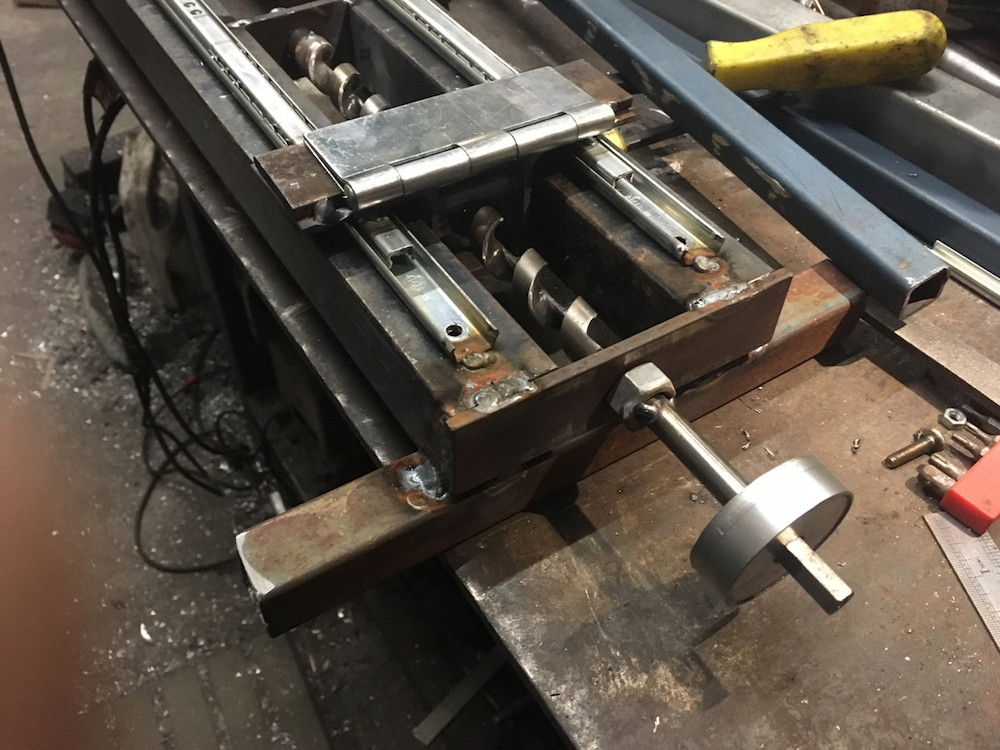

The nut forms part of the carriage, which is mounted to two linear bearings. For this project I have used two heavy duty drawer rails. These are a primitive linear bearing which should be easily available in most places. Given that there is relatively low tool load these should work fine.

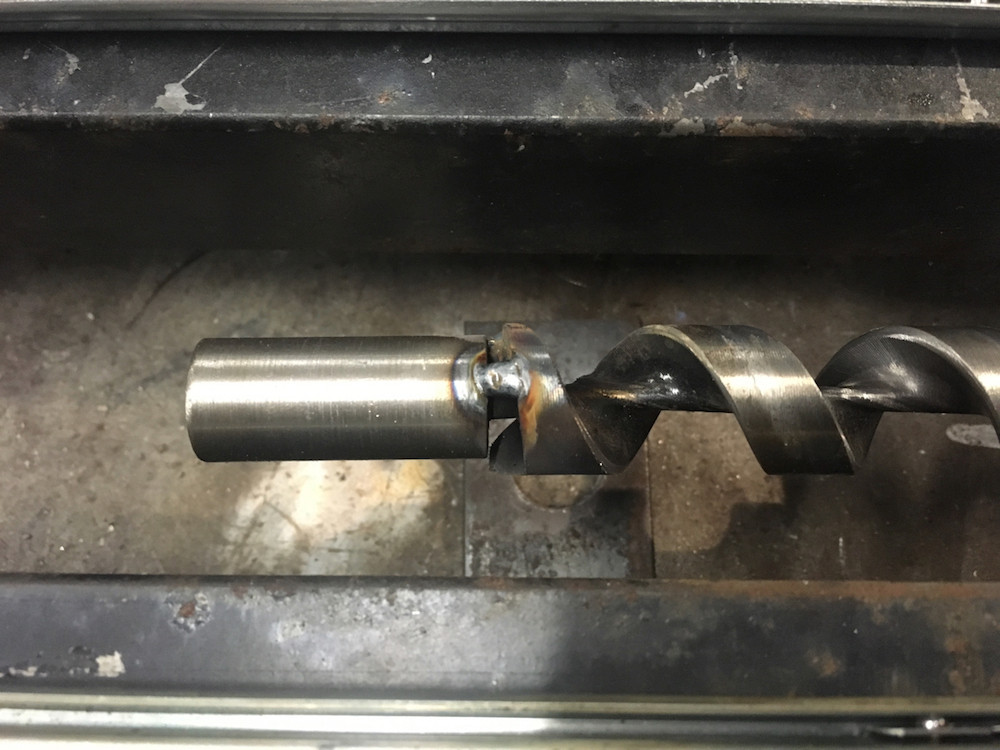

I modified my auger by welding a length of round bar to the end. This does two things. It provides a spigot that allows me to mount the auger between two plates, effectively turning it into a lead screw, and it also allows me to attach a coupling to it so that I can mount the workpiece.

The finished table

The rails mount to two lengths of RHS. these in turn are welded to some simple RHS 'feet', these feet help to keep the nut clear of the table. The auger is held at both ends by flatbar with holes to retain the auger shaft and spigot. I welded a nut hard up against the shaft end of auger to stop it moving back and forth.

The carriage mounts to the two drawer runners which are tacked to the top of the RHS Frame. If you are using RHS for your nut, the two side rails need to be mounted approximately 50mm apart with just enough clearance for the nut to slide along in between them without binding, but not so much that the pins can fall out.

I made a simple handle from aluminium with a hex hole in it, but it is easier to make a crank style handle from round bar and weld it to the end of the shaft.

Here's a video of it working. The bit of bar I welded into the end of the auger needs to be straightened so ignore the wobble it has. The overall result is a fairly tight mechanism without any play

Problems Caveats and Improvements

Nut Design

I made my nut overly complex. It would have been better to make it from a small section of RHS - basically an offcut from the body. With the nut mounted in between the side rails the nut pins would be held captive.

Auger length

The length of the finished screw is limited by the table travel, which in turn is defined by the auger length. You could theoretically make a screw twice the length of the table travel by turning it around and machining it one half at a time. My original design had the workpiece in parallel to the table, which meant that it could be indexed along, theoretically allowing you to produce a screw of infinite length. Not an issue as such, but a consideration. I also lost a bit of travel due to the design of my nut sticking out below the bottom of the side rails and hitting the 'foot'. The RHS nut above does not have this issue

Bearings:

If you are making one or maybe two extruder screws from this machine I think that it will be fine without bearings, but if you are planning to go into production with this machine and make a whole bunch of screws, then bearings are probably a good idea. The size of the bearings is an issue as depending on the size of your auger and therefore bar diameter you will most likely (almost certainly) find that the bearings need to fit too close to each other. This issue requires some clever thinking to be able to solve such as using smaller bearings or bushes instead of bearings or maybe staggering the bearing mounts.

I also peened the bearing mounts to retain them in position, this was a quick and dirty solution and not ideal.

3D Printing & Alternate Construction Techniques

You could theoretically 3D print the nut assembly. This is not technology that is available everywhere but does potentially make creation of this device simpler. I may make a design for a 3D printed version if the actual trials are successful.

You could also use extruded aluminium for the frame and carriage, this would provide a simple bolt together assembly. The design is so simple that it does not really need a design.

Workholding

The next part is to create the tool holder, profile gauges and method of workholding.

Essentially the workpiece (Steel Bar) is held in line with the auger by a coupling in the space on the left of the machine.

All will become clear in part 2

Automatation

You could theoretically put a stepper motor on the end and program an Arduino to traverse the table up and down without the need to stand there and turn the handle. Equally you could also use a regular motor and limit switches to reverse the direction.

You could also use a stepper motor to control the depth of cut, which is an issue we are yet to encounter, but one to be considered.

/DM